An inspiring story from Roger Jones, Neuroendocrine Cancer Survivor and Author

The dragon boat had restored our hope as the rulers of our lives.

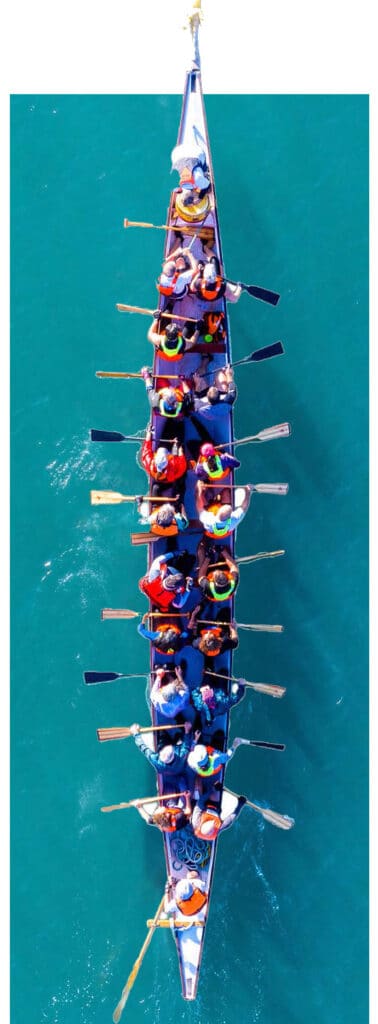

I was sitting in a narrow, wooden forty-eight-foot-long dragon boat surrounded by nineteen other cancer survivors, ready for the race of our lives. As the sole cancer-survivor team in our division, our challenge to win would be a steep uphill battle. And as with my brave teammates, my own body was weak from recent high-dose radiation treatment. We were a group of normal ordinary people attempting to accomplish something extraordinary. We didn’t come to win; we came to survive.

I was sitting in a narrow, wooden forty-eight-foot-long dragon boat surrounded by nineteen other cancer survivors, ready for the race of our lives. As the sole cancer-survivor team in our division, our challenge to win would be a steep uphill battle. And as with my brave teammates, my own body was weak from recent high-dose radiation treatment. We were a group of normal ordinary people attempting to accomplish something extraordinary. We didn’t come to win; we came to survive.

I was a successful businessman and an ex-jock. To my unfathomable surprise, this audacious crew of men and women had become my new family. The heat index in the balmy city of Chattanooga, Tennessee, was a hundred plus. As I looked up the boat at my teammates, I witnessed sheer determination. But I was scared. Had I pushed myself too hard? My body was weakened by malignant tumors and abhorrent treatments. Three full days of racing?

A year earlier, we’d lost a teammate to this mad disease— cancer. Our grief was still raw. Some of us sensed the walls of death closing in, and this competition could well be our final effort for a victory among the tribulations of our lives. Our year-long training had been intense, and we were determined to win. Like the other dragon boat teams, we were trying to find the perfect combination of timing, power, and stamina. But unlike our competition, our training was interspersed with radiation and chemotherapy, so I prayed for strength.

I was competitive by nature and training. My personally prescribed therapy was to turn to the calming waters of the Charleston rivers. I felt lucky to wake each morning to a stunning view of the Cooper River and the spectacular cable-stayed bridge with its diamond-shaped towers that, for many Charlestonians, defined our hometown. Maybe it came about with my life-threatening diagnosis, but somehow my tumors made me more aware of the intricacies of my body, and I looked at things in a new way. The river, with its mighty current and ever-changing tides, seemed to connect my teammates like arteries connecting the body’s organs and muscles; when I paddled it momentarily freed me and my teammates from our terrible illnesses. Could a river bring healing? I hoped and prayed so.

Dragon boat racing is a two-thousand-year-old sport that originated among the fishing communities in southern-central China along the Yangtze River. The sport boomed as an international sport in the 1980s, with thousands of cancer patients becoming participants during the 1990s, as the sport was recognized for improving healing from the vile cancer treatments through physical exercise and team camaraderie. Our crew of twenty cancer-ridden paddlers sat knee-to-knee in ten rows in this lengthy, slender canoe, ten paddlers extending their bodies heavily over the boat’s starboard side and ten over the port. A drummer sat on a small wooden seat at the bow, banging a cadence to synchronize and motivate the paddlers. A steersperson stood at the stern, using a twenty-foot oar to guide the canoe, finding the straightest possible path along the racecourse.

The weekend’s festival was a colorful celebration of life. Thousands of spectators lined the Tennessee River to watch. The boats were made of teak, imported from the Far East, and decorated with a mythical Chinese dragon head and tail. Red-and-gold decorative scales were delicately painted along the hull.

Our team was competing for the over-fifty mixed men’s and women’s national championship. Eight women and twelve men would paddle as one. We’d learned to feel the surge and the glide of the boat. We’d tapped into the canoe’s innate rhythm. The winners would earn the privilege of representing the United States at the International Dragon Boat Races in Hong Kong, China.

Twenty anxious paddlers crouched over the canoe’s gunwale with the blades of our paddles buried deep in the water. Our emotions dangled in suspense as we anticipated the starter’s horn. Three additional boats, in lanes separated by buoys, also intently awaited the signal. There’s probably nothing scarier than sitting at the starting line of a national championship race. A voice shouted, “Ready, ready. We have alignment.” The words vibrated like a tsunami across the smooth water. The muscles in my shoulders contracted with tension. The horn finally blew, and twenty paddles forced through the water in perfect unison. Our drummer pounded hard to create the rhythm for our stroke and screamed, “Up, up, up!” Each paddler’s blade entered and exited the water like the melody of a great orchestra. The water boiled all around the sides of our highly decorated red-and-gold canoe.

I saw Mark, two seats ahead, a tall, slender man with stage four colon cancer. He paddled with a custom-made belt that secured the pouch containing his colostomy and ileostomy. In front of him sat Linda, an ovarian cancer patient who’d long outlived her doctor’s prognosis. In front of the boat was Laurie, a courageous breast cancer survivor. She paddled with a passion to represent all breast cancer patients. Bob, who sat in front of me, had disfiguring neck surgery for jaw cancer. Bob paddled with a feeding tube and a patch over his tracheotomy. Their courage inspired me.

The intensity of my stroke increased as I watched the faces of my friends scowl in pain. My teammates had learned the power of teamwork and the perseverance of pressing through our physical obstacles. But mostly we’d learned to forgive. To forgive ourselves and others. We’d learned forgiveness was the foundation for all miracles. We prayed for miracles. Miracles for healing…yes, but mostly to survive…no, thrive with our disease.

Cancer had stolen my teammates’ mastery of their bodies. But the dragon boat had restored our hope as the rulers of our lives. We were learning that perfect harmony can be made out of broken things and broken people. It would be the lesson of our lives.